What I Learned About Nasal Obstruction From 1,000 Patients

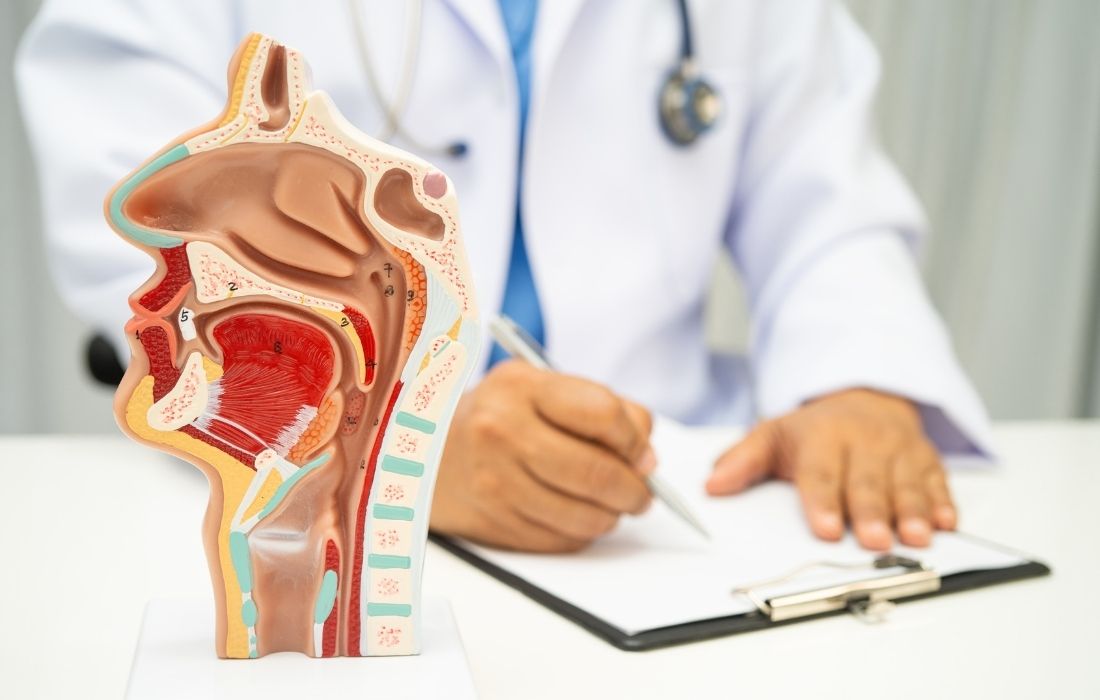

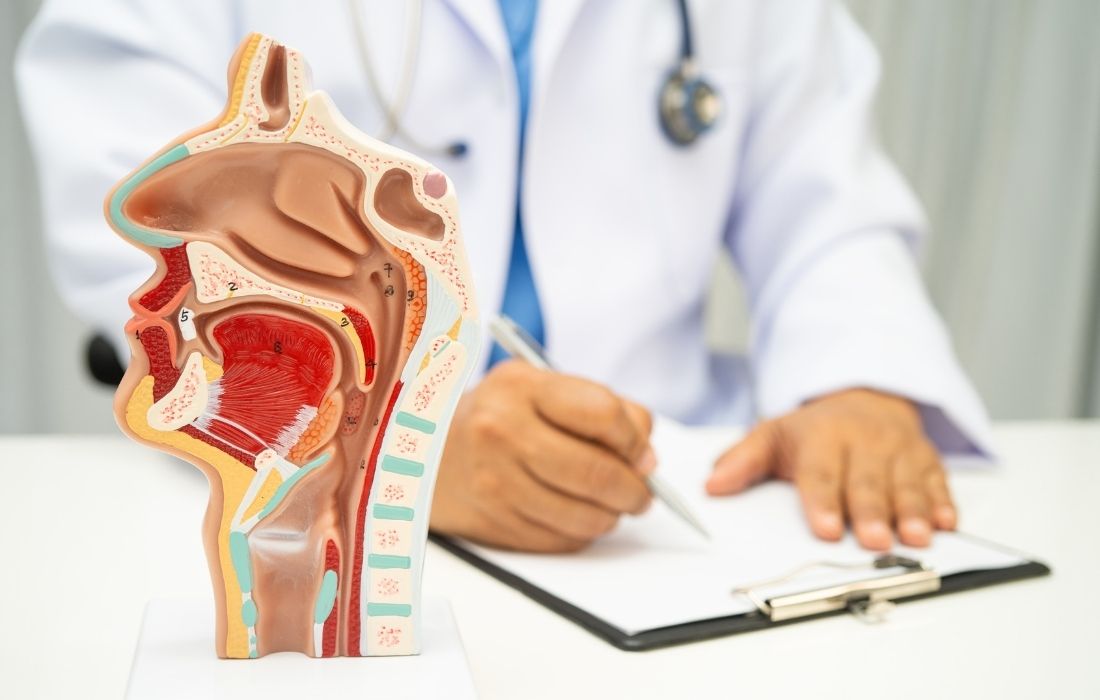

A young woman sat across from me, shoulders tense, eyes tired. She told me she had visited four different doctors in six months. Each visit ended with a different explanation for why she could not breathe through her nose.

One blamed allergies. Another suggested a deviated septum. The third recommended nasal sprays. The fourth said it was all in her head.

That pattern is common. Many patients with nasal breathing problems bounce between clinics for months or years because evaluation often lacks a consistent structure. Instead of a comprehensive nasal evaluation, clinicians may focus on one likely cause and stop early.

After evaluating over 1,000 patients with breathing difficulties, I learned that successful nasal obstruction evaluation requires a systematic approach that many doctors do not perform in full.

The most reliable results come from a three-layer process: a complete patient history, a structured physical exam, and strategic testing used only when it answers a specific question.

The fatal flaw in most nasal obstruction evaluations

Many evaluations fail because they rely too heavily on symptoms alone. Patients describe what they feel, and clinicians try to label it quickly. The problem is that nasal obstruction is subjective, while the underlying cause can vary widely.

According to a study, nasal obstruction is the subjective perception of discomfort or difficulty in airflow through the nostrils and may affect up to 30%–40% of the population. The same position paper explains that causes may be local or systemic, and can be anatomical, inflammatory, neurological, hormonal, functional, environmental, or pharmacological.

So why do symptom-only decisions fail so often?

Symptoms overlap. “Stuffiness” can point to:

- Rhinitis

- chronic rhinosinusitis

- turbinate hypertrophy

- septal deviation

- nasal valve problems

- medication effects

If the clinician treats the symptom without confirming the cause, the plan can miss the true driver.

Subjective complaints do not always match objective findings

Patients often identify a side that “feels blocked” and assume that side is the main problem. However, research shows mismatch is common.

According to a 2021 study, symptoms do not correlate well with the severity and location of obstruction on exam. In their study, 34% of patients perceived the opposite side as most obstructed compared with what the physician found on physical exam. The same study also found low agreement among otolaryngologists reviewing the same endoscopy videos when describing laterality, severity, and the main site of obstruction.

This supports a key practical point. A nasal obstruction diagnosis should not be based on symptoms alone. Symptoms guide the workup, but they should not end it.

Cognitive bias can push clinicians into early conclusions

Symptom-based shortcuts also make it easier for bias to shape decision-making. Clinicians can anchor early and then look only for evidence that supports that first assumption.

According to a study, common cognitive biases affecting clinical reasoning include anchoring bias and confirmation bias. When those biases drive an evaluation, the clinician may “see only what they expect,” and may miss other relevant pathology.

The three-layer diagnostic approach that changes outcomes

A consistent approach reduces missed causes and improves the quality of nasal obstruction assessment. In this framework, diagnosis is built in three layers:

- Layer 1: Complete history

- Layer 2: Structured physical examination

- Layer 3: Strategic imaging and testing

This is the point where I rely on my own clinical approach learned from evaluating 1,000 patients. A systematic nasal examination process prevents “single-cause thinking” and forces a complete assessment before the plan is made.

Layer 1: The complete patient history that most doctors skip

In a strong nasal obstruction evaluation, history is not a quick checklist. It is a directed investigation.

The same study above shows that directed study of medical history and physical examination are key for diagnosing the specific cause of nasal obstruction. Another research also emphasizes that clinical history and examination often identify the cause and guide further investigations and management.

The 12 questions used in a systematic protocol

These are the exact history items that shape a comprehensive nasal evaluation:

- Is obstruction unilateral, bilateral, or alternating?

- Is it intermittent or persistent? Is it acute or chronic?

- Is it seasonal or diurnal?

- Are there triggers such as smoke or pets?

- Is rhinorrhea present? Is it clear or purulent?

- Is facial pain present? Is fever present?

- Is smell or taste altered?

- Are atopic features present such as itching, watery eyes, sneezing? Is there asthma or dermatitis history?

- Are there red flags for neoplasia such as unilateral obstruction with epistaxis? Any ear symptoms suggesting Eustachian tube involvement? Any paresthesia, diplopia, or trismus?

- Is there a history of sinonasal surgery?

- What medications are being used, including those known to contribute to nasal symptoms?

- Are there relevant social exposures such as smoking, alcohol, illicit drug use, or occupational dust exposures?

Do all 12 always matter? Not equally. But skipping them can hide the cause.

Medication history can uncover hidden causes

Medication and spray history often changes the diagnosis.

There are medication groups associated with nasal obstruction, including:

- antithyroid drugs

- oral contraceptives and other estrogens

- multiple antihypertensive classes

- NSAIDs

Drug-induced non-allergic rhinitis is also emphasized in review literature. According to a study, multiple drug subtypes can induce rhinitis, and awareness of drug lists plus careful medication history is important for diagnosis.

Rhinitis medicamentosa is a specific example with a clear pattern. Rhinitis medicamentosa is inflammation caused by overuse of topical nasal decongestants, often beyond 7 to 10 days. They also note that diagnosis is clinical and depends on careful symptom history and examination.

Layer 2: The Physical Examination Framework That Reveals Hidden Pathology

Once history narrows the differential, the exam must test it. A “quick look” can miss important sites of obstruction.

Start with:

- external examination

- then evaluate internal anatomy with anterior rhinoscopy

- and use nasal endoscopy in specialist settings when diagnosis remains unclear

External examination and airflow dynamics

External exam looks for deformities and functional clues. The same study above describes assessing nasal tip ptosis, manually elevating the tip to see if airflow improves, watching airflow during inspiration, and evaluating for nasal valve collapse.

They also describe Cottle’s manuever as a way to assess whether symptoms relate to nasal valve issues. In that maneuver, the cheek is held to prevent collapse, and the patient reports whether airflow improves.

Internal examination with anterior rhinoscopy

Anterior rhinoscopy requires good lighting and a speculum, and they describe an alternative “pig nose” technique in primary care settings.

They also describe key mucosal findings: pale, boggy mucosa can fit allergic rhinitis, while red, edematous mucosa appears more often in infective or vasomotor rhinitis.

Why nasal endoscopy often changes the diagnosis

If diagnosis remains unclear, fiberoptic nasal endoscopy may be needed to examine posterior areas. Research also supports that endoscopy can detect pathology missed by other methods.

According to a study, nasal endoscopy detected early polyps in some patients who had normal CT imaging reports. They also reported CT missed some deviated septum cases. Their conclusion reinforces that diagnostic nasal endoscopy can reveal sinonasal pathology not seen with routine speculum examination and may detect changes missed on CT.

Pre- and post-decongestant examination and preparation

Specialist endoscopy is usually performed after topical preparation with a decongestant and local anesthetic spray.

One study compared preparation approaches and found that using decongestant plus anesthetic together produced the lowest endoscopy pain scores in their study, while decongestion was best achieved with decongestant in their setup.

Documentation reduces inconsistency

A study showed low agreement among similarly trained physicians interpreting endoscopic exams for obstruction details. That supports a practical need for structured documentation so findings can be followed consistently across visits and across clinicians.

Layer 3: Strategic use of imaging and testing in nasal obstruction evaluation

Tests should support decisions, not replace clinical work.

Both subjective assessment tools and objective estimation methods. The study mentioned also note little correlation between them and recommend viewing them as complementary, not exclusive.

When CT is essential and when it is not

CT is the preferred imaging modality for the nose and paranasal sinuses, and MRI is used when CT is inconclusive or when further soft tissue characterization or extension assessment is needed.

Another study adds that CT is indicated when there is a suboptimal response to medical treatment for mucosal diseases or when red flags are present, including:

- persistent unilateral obstruction

- epistaxis

- pain

- orbital symptoms

- neurological symptoms

They also note that CT helps assess extension of sinus disease into the orbit or intracranial cavity.

Objective airflow tools and the mismatch problem

Objective measurement tools can be helpful, but symptom correlation is often weak.

- One study reported that objective outcome measures and patient-reported measures are poorly correlated in sinonasal disorders. In their review, peak nasal inspiratory flow (PNIF) showed the strongest correlation with patient-reported measures for nasal obstruction among the tools discussed, while rhinomanometry often showed lack of correlation.

- Another study evaluated PNIF as a screening tool and found good sensitivity and high negative predictive value at a cutoff of 90 L/min, but low specificity and low positive predictive value. They also reported low agreement between PNIF and symptoms of blockage and between PNIF and presence of sinonasal disease.

- A 2023 study also describes that rhinomanometry and acoustic rhinometry are major objective assessment methods, but they note a lack of consensus across studies and differences in standardization efforts.

Allergy tests, microbiology, and trial treatments

The same study describes allergen-specific IgE blood testing when allergy is suspected and note that food mix testing can produce false-positive results. They also describe swabbing pus when present to guide antimicrobial therapy.

Treatment is based on cause and can be pharmacological when etiology is inflammatory or functional, with surgery considered when medical therapy fails or when other approaches are not possible. This supports the careful use of treatment trials as part of nasal obstruction assessment, as long as trials are tied to a clear diagnostic question.

The Integration Phase: Putting It All Together for Accurate Diagnosis

The most important step is integration. Without it, a patient can end up with fragmented care.

After evaluating over 1,000 patients, I rely on integration rules that prevent single-cause assumptions and help prioritize when multiple findings coexist.

Individualized treatment is important and combinations of medical and surgical approaches may be necessary. Most causes can be diagnosed with history and exam, but persistent symptoms, uncertain cause, or suspicion of neoplasm warrant further investigation and referral.

Common diagnostic patterns with systematic evaluation

When all layers are completed, patterns often become clearer:

- Mixed mucosal and anatomical contributors can coexist, so obstruction can persist if only one factor is treated

- Endoscopy can reveal posterior pathology that routine viewing misses

- Symptoms can mislead laterality or severity, so exam structure matters

- Medication effects can be hidden unless asked directly

- Overuse of topical decongestants can produce rebound congestion requiring a different plan

Communication framework that supports understanding

Patients often feel dismissed when their symptoms do not match test results. Subjective and objective tools may show little correlation but can be complementary. Explaining that mismatch early helps patients understand why a systematic nasal obstruction evaluation includes both what the patient feels and what tools measure.

Final word

A reliable nasal obstruction evaluation depends on structure: complete history, thorough physical exam, and strategic testing. Research supports this foundation. Directed history and exam are key and frames subjective and objective tools as complementary. History and exam often identify the cause and guide management, with escalation when needed.

If nasal breathing problems have persisted despite prior treatments, it is reasonable to seek a comprehensive nasal evaluation that follows all three layers. A complete nasal obstruction assessment reduces missed causes and supports clearer, more consistent care.

FAQs nasal obstruction evaluation

Why is nasal obstruction so hard to diagnose?

Because “blocked nose” is a feeling, not a diagnosis. Many different problems can cause the same symptom. If a doctor stops after finding one possible cause, the real driver can be missed. A full evaluation needs history, exam, and testing working together.

What does a proper nasal physical exam include?

It starts with the outside of the nose, then looks inside with anterior rhinoscopy. The doctor checks airflow, septum position, turbinates, and lining color. If the cause is still unclear, nasal endoscopy is used to see deeper areas.

What is nasal endoscopy, and when is it needed?

Nasal endoscopy uses a thin camera to look deep inside the nose. It’s used when routine exam can’t fully explain symptoms. Endoscopy often finds problems that are missed with a quick look or even imaging.

What is the Cottle maneuver used for?

It helps check nasal valve function. The doctor gently pulls the cheek outward to prevent collapse. If breathing improves, it suggests the nasal valve may be contributing to obstruction, not just internal swelling or septum shape.

What are red flags with nasal blockage?

Red flags include one-sided blockage with bleeding, foul smell, numbness, vision changes, facial pain, or nerve symptoms. These signs need urgent evaluation and often imaging to rule out serious disease.

When is a CT scan actually helpful?

CT is not routine. It’s most useful when symptoms persist despite treatment, red flags are present, or surgery is being considered. CT supports decisions but should not replace a careful history and exam.

Can medications cause nasal obstruction?

Yes. Several drugs can worsen nasal congestion, including some blood pressure medicines, hormones, NSAIDs, and nasal sprays used too long. This is why a full medication history is critical during evaluation.

Why do some people stay blocked even after treatment?

Often because more than one cause is present. For example, swelling and structure problems can coexist. Treating only one layer may help briefly but won’t solve the full problem. Integration of findings leads to better outcomes.

Sources

- Valero, A., Navarro, A. M., Del Cuvillo, A., Alobid, I., Benito, J. R., Colás, C., de los Santos, G., Fernández Liesa, R., García-Lliberós, A., González-Pérez, R., Izquierdo-Domínguez, A., Jurado-Ramos, A., Lluch-Bernal, M. M., Montserrat Gili, J. R., Mullol, J., Puiggròs Casas, A., Sánchez-Hernández, M. C., Vega, F., Villacampa, J. M., … Dordal, M. T.; SEAIC Rhinoconjunctivitis Committee & SEORL Rhinology, Allergy, and Skull Base Committee. (2018). Position paper on nasal obstruction: Evaluation and treatment. Journal of Investigational Allergology and Clinical Immunology, 28(2), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.18176/jiaci.0232

- Saxon, S., Johnson, R., & Spiegel, J. H. (2021). Laterality and severity of nasal obstruction does not correlate between physicians and patients, nor among physicians. American Journal of Otolaryngology, 42(6), 103039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2021.103039

- Coen, M., Sader, J., Junod-Perron, N., Audétat, M.-C., & Nendaz, M. (2022). Clinical reasoning in dire times: Analysis of cognitive biases in clinical cases during the COVID-19 pandemic. Internal and Emergency Medicine, 17(4), 979–988. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-021-02884-9

- Esmaili, A., & Acharya, A. (2017). Clinical assessment, diagnosis and management of nasal obstruction. Australian Family Physician, 46(7). Retrieved from RACGP website: https://www.racgp.org.au/afp/2017/july/clinical-assessment-diagnosis-and-management-of-na

- Alromaih, S., Alsagaf, L., Aloraini, N., Alrasheed, A., Alroqi, A., Aloulah, M., Alsaleh, S., & Alhawassi, T. (2025). Drug-induced rhinitis: Narrative review. Ear, Nose & Throat Journal, 104(9), 582–590. https://doi.org/10.1177/01455613221141214

- Wahid, N. W. B., & Shermetaro, C. (2023). Rhinitis medicamentosa. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from NCBI Bookshelf: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538318/

- Maru, Y. K., & Gupta, Y. (2014). Nasal endoscopy versus other diagnostic tools in sinonasal diseases. Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head & Neck Surgery, 68(2), 202–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12070-014-0762-y

- Şahin, M. İ., Kökoğlu, K., Güleç, Ş., Ketenci, İ., & Ünlü, Y. (2017). Premedication methods in nasal endoscopy: A prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Clinical and Experimental Otorhinolaryngology, 10(2), 158–163. https://doi.org/10.21053/ceo.2016.00563

- Saxon, S., Johnson, R., & Spiegel, J. H. (2021). Laterality and severity of nasal obstruction does not correlate between physicians and patients, nor among physicians. American Journal of Otolaryngology, 42(6), 103039. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2021.103039

- Whyte, A., & Boeddinghaus, R. (2020). Imaging of adult nasal obstruction. Clinical Radiology, 75(9), 688–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2019.07.027

- Ta, N. H., Gao, J., & Philpott, C. (2021). A systematic review to examine the relationship between objective and patient-reported outcome measures in sinonasal disorders: Recommendations for use in research and clinical practice. International Forum of Allergy & Rhinology, 11(5), 910–923. https://doi.org/10.1002/alr.22744

- Rujanavej, V., Snidvongs, K., Chusakul, S., & Aeumjaturapat, S. (2012). The validity of peak nasal inspiratory flow as a screening tool for nasal obstruction. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand, 95(9), 1205–1210. Retrieved from PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23140039/

- Naito, K., Horibe, S., Tanabe, Y., Kato, H., Yoshioka, S., & Tateya, I. (2022). Objective assessment of nasal obstruction. Fujita Medical Journal, 9(2), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.20407/fmj.2021-029

Related Posts

What I Learned About Nasal Obstruction From 1,000 Patients